Editor’s note: Mentions of the Green River Killer, Downtown East Side Killer, Jeffrey Dahmer, violence, abuse, assault, sexual assault, rape, non-descriptive mentions of death, murder, execution and overdose.

I received Freedom & Prostitution, a book of poetry by Cassandra Troyan, as a parting gift from a friend before she left Berlin for Paris in 2023. She had seen me rapt, thumbing through the narrow and gloriously pink book, on her sunlit couch one morning as I waited for her to get dressed so we could go out into the blustery Berlin wind for coffee. At my friend’s goodbye picnic some months later, I received the book as a gift. I have since read Freedom & Prostitution twice (or is it three times?), cried over its pages, memorized a few key passages, until finally passing it on to another sex worker. This book demands to be read. Troyan’s poetry can be blinding in its ferocity, but sometimes ferocity is what I require as a reader. In the face of a whorephobic world in which violence against sex workers seems to go unchecked, I agree with Troyan: “If you are a prostitute of the/21st century/metaphors are not enough.”

This is a book of poetry about violence. I appreciate Troyan’s willingness to engage with the uncomfortable, because it is real. In contemporary sex worker activism, I notice that there are moments where I feel like we try so hard to move away from being stigmatized as helpless prey or hapless victims of violence, that we forget the importance of how we direct the narrative of violence when it does occur.

At times, this book is a eulogy to the dead and a chronicle of the living. At other moments, it is a reminder of why we have chosen this work in a world where survival means many things, but it especially means money. Troyan writes, “You hate no woman who has found herself in the hustle/discovered talent in the slime/dealing, stripping, fucking/constantly redefining the bottom of everything. The tenuous underpinnings of our work are named, gloriously so, by a point of view which we get to rarely read but always feel: …remember/that you can do almost/anything/for an hour…/You do not want to be saved/You want the end of work not the end of sex…”

At times, this book is a eulogy to the dead and a chronicle of the living.

To me, Troyan’s greatest triumph in Freedom & Prostitution, first published in 2020 by Elephant Press, is their juxtaposition of the murders committed by sex worker & murderer Aileen Wuornos (1989 – 1990) with those of Seattle’s Green River Killer (late 1980s – late 1990s). The treatment of the two cases in the media is an example of the way whorephobia and the politics of victimhood are weaponized by the state against sex workers. Without being clumsy or heavy-handed, Troyan elucidates the demand made on us as sex workers to essentially be the ‘perfect victim’—a term I first heard postulated by activist Miriam Kaba. Troyan writes, “To be innocent is to be closest to dead.” Wuornos, a self-described “hitchhiking hooker,” is the sex worker who would not be a victim, who lived because she fought back and then killed the men who—according to Wuornos—tried to rape her after an agreement was made for transactional sex for a ride home.

One of these men who picked her up, in a country where hitchhiking and picking up hitchhikers began to carry a serious air of impropriety in the 1980s, was a military officer and police chief. This became part of the media circus around her trial and of her inability to claim self-defense in court. To suggest, through claiming her innocence, that a former police chief would engage the services of a prostitute or pick up a hitchhiker, called into question not only his whole career, but the nature of policemen and policing itself. Wuornos, suggests Troyan, then must die—guilty—to protect the system.

It is not lost on me as an American citizen, as a sex worker, and as a woman, that comparatively, the Green River Killer still lives today in 2025 in prison. He lives, eats, and breathes, on taxpayer dollars after having kidnapped at least forty-nine sex workers along the Pacific Coast Highway and destroying them for the sole reason of his pleasure and madness. Wuornos was sentenced to death and executed in 2002 for the crime of murdering seven men she alleged tried to rape her after soliciting her for prostitution on the highway.

“To die tonight, to die in this bed”, is the refrain Troyan writes over and over again throughout the book. As a reader, I began to hear it aloud in my head as a chorus of Muses, in the voices of my fellow sex-workers who have been snatched from the world by violence. It is the gamble of dying, or being raped as a victim and living, or fighting back and living, and then likely dying as the guilty one in the eyes of the law. A strategy of self-defense is generally made for white men in a United States court of law, with rare exception. Wuornos did not garner the emotional support of a nation which will allow, from time to time, a soft, elegant, willowy, and stereotypically feminine white woman to get away with crime if she cries enough and is repentant. As Troyan writes of/to Wuornos, “you were beery, you dressed like a man”. Wuornos was not the type of white woman whose tears could move a jury or judge to paternalistic pity. She was a lesbian, struggled with mental illness, a survivor of extreme violence, working-class, butch, a sex worker, had crooked teeth and thin hair, and dared to claim that men with wives, pensions, and badges had desired her anyways.

The demonization of Wuornos in the media lasted far beyond her death by state execution in 2002; I first learned of the story of Wuornos in 2014, when I was a teenager who possessed an interest in serial killers and prostitution and powerful women. I watched a documentary that was then available on Netflix about her (there are several in existence, the most well-known made by Nick Broomfield). I was sickened by the story of her brutal childhood and the ways in which the dual institutions of state and nuclear family repeatedly failed her. Troyan focuses on Wuornos as a human being, with an understanding which Wuornos was denied throughout the course of her trial.

As a Black sex worker, it is interesting to incorporate the arc of the Atlanta Child Murders (1979 – 1981), which occurred roughly in the same era as the Wuornos/Green River Killer murders and trials. The way in which the majority of the twenty-eight Black victims murdered over a two year period in and around Atlanta, Georgia were characterized as thieves, runaways, homosexuals, and child prostitutes by the police and media, gives further dimension to the realities of stigmatization, violence, and victimhood. Troyan writes, “The destruction of a body. A white body. A brown body. A black body. A body reconstituting its own glue, its own insatiable labors in a contract with foes that holds you beyond choice.” It would have paired with the ways in which some of the Green River Killer’s victims were characterized as disposable, and therefore were not searched for by police, due to their real or imagined status as runaways, Black, Indigenous, or sex workers.

I appreciated Troyan’s lifting up of Marcie Fay Chapman, one of the Green River Killer’s few known Black victims, in their naming of the dead. In reading any book about sex work written by a white person (be they sex worker or civilian), I expect Black sex workers to either be erased entirely or to exist as single sideline characters in a half-hearted attempt at inclusion. Troyan does neither, acknowledging the reality of our different experiences without performing solidarity: “To be white and pretty/To be Black and pretty but with less options.” Black and Indigenous sex workers in the United States & Canada, much like Black & Indigenous civilian women, are at a higher risk for violence by clients and attackers than their white counterparts. The Western seaboard has seen both the Green River Killer of Seattle, Washington and the Downtown Eastside Killer (1995 – 2001) of Vancouver, BC, Canada who both targeted sex workers. The Downtown Eastside Killer was arrested in 2002 (the same year Wuornos was executed by the state), after having murdered at least thirty-three women. He died in prison on May 31st, 2024.

In reading any book about sex work written by a white person (be they sex worker or civilian), I expect Black sex workers to either be erased entirely or to exist as single sideline characters...

Although many of the Green River Killer’s known victims were white female sex workers, the Downtown East Side Killer of Vancouver targeted Indigenous female sex workers. It reminds me of the way in which serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer focused on Black, Asian, and Native American boys and men (some of whom were allegedly sex workers)—because white men know what BIPOC people know, and what the media pretends to ignore: our families and our communities are going to come looking for us when we go missing, but the police will not. The Black prisoners in Dahmer’s cell block also knew this, which is why they chose to summarily do what the state would not, and informally execute Dahmer three months after his imprisonment.

Troyan also skillfully avoids providing any kind of pornographic canonization of the Green River Killer in Freedom & Prostitution, a phenomenon which happens all too frequently with serial murderers like him and Dahmer (consider the recent Netflix show, Dahmer). Troyan barely mentions his real name and instead focuses their energy on naming and fleshing out the lives of the sex workers he murdered. This too, is worthy and good; we often remember the names of the serial killers, who live on as Boogeymen or objects of fascination (gaining followers, gifts, and even wives from the remoteness of their cell blocks when they are allowed to live), but the names of the victims fade into obscurity. This erasure of the dead, and the brutality of their passing, also helps to conceal the reality of the crime.

While the intended theme of this book appears to be the indication of sex work as a means for the abolition of all work, I found the book’s tangible message to be it’s addressing of gendered violence against sex workers by the state and individuals through poetic storytelling. It was painful, and important, for me to read one of the many interwoven narratives in the book: a story based on the 2014 attack of Christy Mack, an adult film star, by her ex-boyfriend, an MMA fighter and fellow former pornographic film actor. Troyan’s lyrical storytelling was interspersed with a narrative about a sex worker trying to escape an abusive relationship with an ex-military man. There was reference to the apparent real-life case of an Australian sex worker, who was charged with murder after she fulfilled her client’s request to shoot him up with heroin and he overdosed.

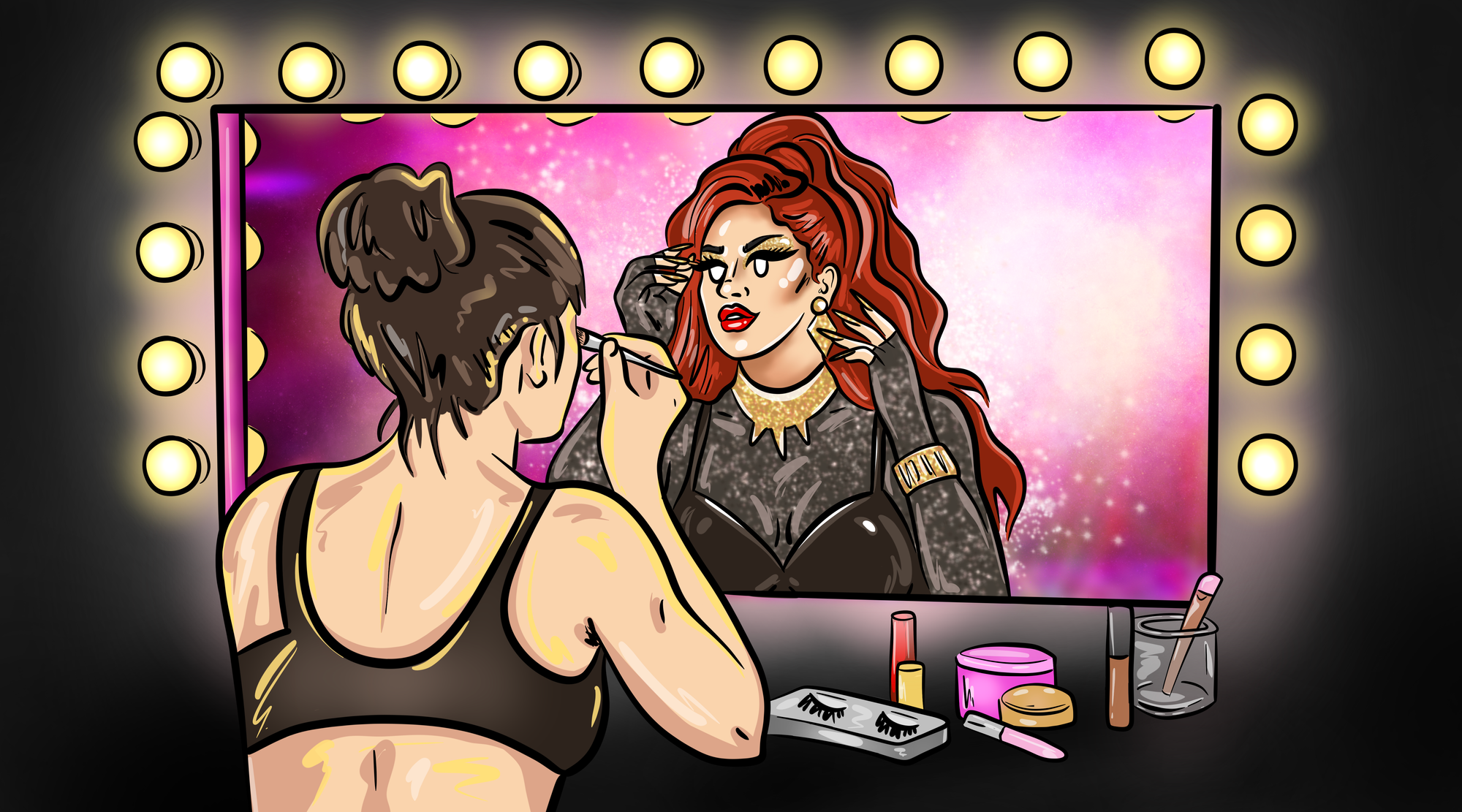

Freedom & Prostitution is a masterfully written legacy of sex work, abolition, and violence. I personally wish to see it, or help it become, realized as a performance play with sex workers in the future. The subject matter is very difficult, and there were times I felt I had to put the book down to recover myself—yet, I could not bring myself to put it down. Based on a cursory internet search, I am unsure if Troyan is a sex worker, although their professional profile demonstrates collaborations with sex workers in the arts. Therefore, it is hard to evaluate what the implications would be if this book had been written from a civilian’s eyes. Even so, this is a book of poetry that was passed to me as a gift because of its preciousness. After I finished reading the book, I passed it to a colleague from my old club and informed her it was her task to pass it on to another worker when she finishes. This is a book to be purchased, and pressed into the hands of your friends and colleagues, saying, “you must read this!” in the hiss under your breath as your manager walks by the open dressing room door. This book must travel through dressing rooms, backstages, sets, photoshoots, during the fellowship following recovery meetings, and it must be discussed by our community—especially over late afternoon coffees in those few precious hours we steal from the state and our work to live our ordinary lives.

Get your copy of Freedom & Prostitution here.

Are you a sex worker with a story, opinion, news, or tips to share? We'd love to hear from you!

We started the tryst.link sex worker blog to help amplify those who aren't handed the mic and bring attention to the issues ya'll care about the most. Got a tale to tell? 👇☂️✨