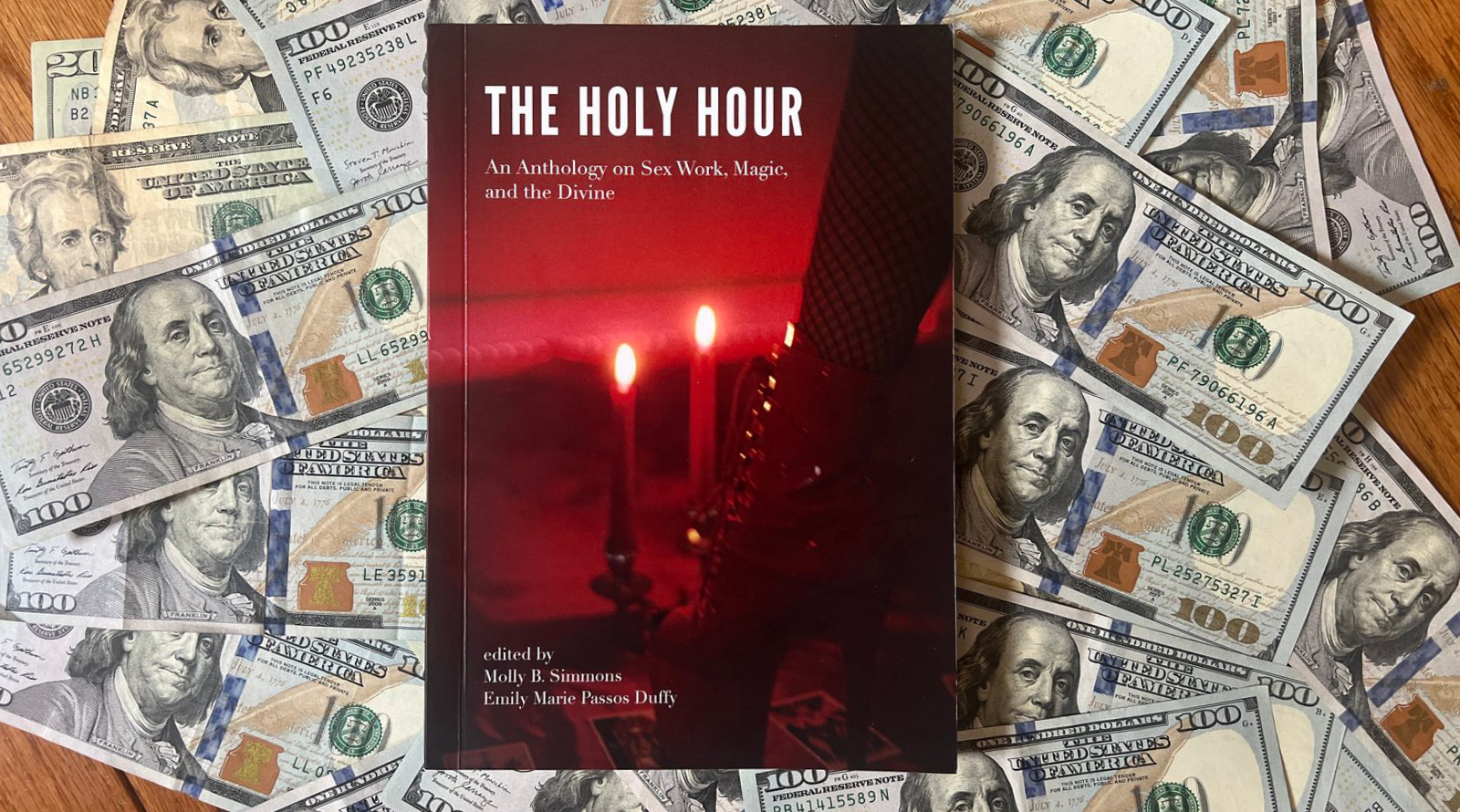

I wept. I laughed. I chanted. The Holy Hour: An Anthology on Sex Work, Magic, and the Divine (THH) is a collection of visual art and writings by sex workers, edited by Molly Simmons and Emily Marie Passos Duffy. It was released in 2024, and at the time of writing this review, I have just finished reading my free sex worker copy (available by emailing the publisher, Working Girls Press, directly through their website). It is rare in my life that I have seen the intersections of sex work and magic, media, mental health, kink, religious structures, and personal spiritual practices explored in a multi-genre format like this.

The anthology consists of contributions from forty-five different workers from across the United States. The majority of the entries in the anthology were impressive, as was the way in which the entire collection was edited by Simmons and Passos Duffy into a cohesive ‘spell book.’ Workers who—to paraphrase Simmon’s editor’s note—find themselves consistently pulled between the contradiction of the genuine healing they notice their clients receiving from the work and the ways in which they at other times serve as disposable containers for clients’ personal issues, will find themselves bewitched by this book.

Particular standouts from the anthology are Evie Vigil’s opening essay and research piece Quantum Whore, Daemon Derriere’s dystopian erotic fiction chapter Ishtar’s Angel, Chloe Williams’ essay POV of a GTA Stripper, nawa a.h.’s multi-genre experimental free verse poem am i hot enough to kill, which closes the anthology, Hunter Leight’s pasted-in zine of affirmations and prayers A Sex Worker Liturgy, Julia Laxer’s essay JULIA ST., Lucy Khan’s meditation on the divine nature of Full Toilet Training (FTT) in her essay Holy Shit, Gia Jones’ prose-poem Jesus Loves Strippers, and Madeleine Blair’s essay Thin Walls, an account of a group of sex workers who get scammed by an Instagram witch into a less-than-promised retreat on a Puerto Rican island.

It is rare in my life that I have seen the intersections of sex work and magic, media, mental health, kink, religious structures, and personal spiritual practices explored in a multi-genre format like this.

One point of strain for me, however, was that references to Catholicism and Protestantism were predictably over-present in this anthology. I noticed this in the content of submissions and the nonetheless beautiful photographs by Maria LaSangre, of contributors holding crucifixes and wearing vinyl fetish gear. It is of course true that Catholic imagery plays a dominant role in sex work, the least of which are costumes and role playing. It was more refreshing to read the contributions about growing up in the Mormon church in Altar of Ecstasy by Jessie Sage, and those from Jewish sex workers Evie Virgil and Alison Glass who explored Torah stories of biblical figures associated with sex like Tamar and Lilith.

Notably missing for me from THH were contributions which explored the richness of Islamic, South Asian, or SWANA (Southwest Asia and North African) spiritual heritage in sex worker’s lives and work. Contributor Elena Egusquiza did mention the interesting point that Buddhism is the only major world religion which does not explicitly condemn sex work in their essay The Sacred Prostitute: Sex Work as a Tool for Resistance, Liberation and Healing, but from a point of research rather than personal heritage or practice. Similarly, contributor Britta Love briefly mentioned a possible connection from southern India to the idea of the sacred prostitute, Devadasi, but this would have been more powerful, for me, to learn about from a sex worker of Indian heritage in relation to their own work. I do wish to applaud what I felt was a comparatively high representation of Asian-American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) workers in this text, whose voices are often overlooked in our industry. Yet as a Black sex worker I was left with a very white—albeit, still pleasant—taste in my mouth. I appreciate that the contributions by Black sex workers that I did notice were able to just ‘exist’ in the anthology, without having to perform as a Black perspective. Rather than some contributors having multiple submissions, I feel that duplicate spaces could have been dedicated to exploring any missing perspectives.

Notably missing for me from THH were contributions which explored the richness of Islamic, South Asian, or SWANA (Southwest Asia and North African) spiritual heritage in sex worker’s lives and work.

The photograph of Olivia Ives, by Kelsey Rellas, Circe Offering the Cup to Chad, was striking. Ives is sheathed in what we think of as Grecian or Roman-style robes, clear Pleasers, and seated in front of a mirror – which could be the archetypal magic mirror of our dreams complete with chilling statues of goblin-style figures. Yet the mirror, the scene itself, is one which we know from many strip clubs, brothels, and kink spaces: the mood lighting, the statues, the carpet with its squiggling design meant to hide dirt and body fluids, the eternal glow of the ATM machine, the sense of entering a space which could turn profane or divine at any second.

Ives has done a wonderful job of translating the original image of Circe, a witch from Greek mythology, handing a cup of wine laced with herbs which will turn a mortal man into a pig. Ives holds up a cocktail to Chad, who, like many clients, will have their most primal urges and desires brought to the surface by us. The image’s composition caused me to think anew of the ways in which sex work spaces frequently imitate the aesthetics of Grecian temples and Christian churches, with curtains like confessionals, carved statues & idols, spaces to make offerings, libations, and fire-like lighting. And of course, how many of us know a sex worker named ‘Venus’ or ‘Aphrodite’?

Two of the most gorgeous photographs I have literally ever seen in my life were in this anthology, taken by Maria La Sangre. Dominatrix Cléo Ouyang is in a metallic turtleneck cling dress with a high-split, wet hair, and gleaming makeup as they exude power over the submissive who is kneeling before them. The sub’s hands are tied in exquisite rope bondage and their head is sheathed in a swathe of gossamer fabric. It was strange to me, in such a visually pleasing anthology, that there were not more contributions about the unique and specific work of creating visual glamour and the spellcasting online/webcam models must do. However, if this is just the first of what seems to be a projected multiple editions of the anthology, then I would call it a triumph.

If this is just the first of what seems to be a projected multiple editions of the anthology, then I would call it a triumph.

There were many noteworthy insights about our work in this anthology, which included Madeleine Blair’s elucidation of the “princess and prey” dynamic found in stereotypes about sex workers, and Chloe Williams’ forthright and necessary observation on the multiplicity of stigmas we experience:

“Sex workers are fuckable tropes, idolized in our damnation. We are worshipped as goddesses by adoring lonely men, damned jezebels infecting righteous men with lust, girlboss queens owning our sexuality capitalizing off of the patriarchy, anti-feminists upholding the patriarchy by objectifying ourselves to the male gaze, shadowy figures in dim street corners leaning into cars asking men if they’re “looking for a good time,” or tragic figures of fallen women in literature. Our stories are either great triumphs or heartbreaking tragedies, never as ordinary humans trying to get through the day.”

Equally impressive were the conclusions drawn by contributor Evie Vigil in their essay. Virgil meditated on time, the archetype of the sacred prostitute, and the illusory veil which separates our world from that of civilians and clients. Uriah Fate’s play on the archetypal ‘Fool’s Journey’ from tarot, a piece entitled The Whores Journey, meditated on the High Priestess card in tarot as a representation of the mentors/teachers we encounter in sex work who enable us to survive—and thrive—in this industry, and was a welcome inclusion.

I held my breath throughout Britta Love’s graceful exploration of the oft-taboo topic in our community—romantic relationships between workers and clients—in their piece, Dreaming the Revolutionary Sacred Whore: Doing the Work of the Goddex. While a primary focus of the piece was their positioning of themselves in sex work as a sacred healer and the formal, as well as personal, journeys they have taken to professionalize themselves as such, the essay’s true shining pearl was Love’s elegant writing style and their neatly honest account of falling in love with a client.

I found myself weeping and chanting aloud at some of the prayers and affirmations in Hunter Leight’s A Sex Worker Liturgy, yet the piece which lingers with me the most in my post-reading glow is Daemon Derriere’s Ishtar’s Angel, a dystopian erotic fiction. The first chapter is included in the anthology and the subsequent three can be read on Derriere’s Substack. The first-person account of life in a post-apocalyptic death-brothel (like the ‘assisted exit’ center in the classic dystopian 1973 film Soylent Green, but with boobs, LSD, and cock) in a world ruled by AI bots demonstrates the potential for sex worker art and writing to highlight the very real intersections and critical concerns of artificial intelligence, data privacy, climate collapse, the crumbling of nation-states, and sex work. I anxiously await the full-length novel of Ishtar’s Angel.

“Sex workers are fuckable tropes, idolized in our damnation. We are worshipped as goddesses by adoring lonely men, damned jezebels infecting righteous men with lust..."

The dichotomy of the front and back cover photographs feels like a nod to the hidden, at-times opposing, ways of our work. The front cover is a photograph by Layla Tobin of a red lit and deeply sensuous tableau: a slick-red vinyl pleaser is reflected in a floor length mirror alongside a triad candelabra of scarlet flames. This is the façade we present to clients, but it is also reality. Sex workers are skilled artists, designers, conjurers of scenes, and have considerable personal style. More often than not, we understand the full spectrum of what beauty is, and most importantly, how to transmute beauty from a handful of previously unrelated objects, or from very little at all—in contributor Lucy Khan’s words, we are master alchemists, able “to turn shit into gold.”

The back cover is starkly black and white, and of a scene so tender it made me press my hand to my heart, because I have seen and participated in it dozens of times: one person handing another a pack of moist towelettes or baby wipes, in a backstage-type setting. And this, too, is the reality of our work: a coven in which we are all bound, cobbling together and lending one other the tools we need to keep our spells going. We work to hold up the sky in our lives, much as the witch Circe did over her island Aiaia to protect herself from the wrath of Athena. Or, as Uriah Fate discusses, we take the time and care to initiate the newbie into the wisdom of the High Priestess. We, as sex workers, are bound not by blood but by ability and by work. Our magic is one of survival.

If, as Simmons says in their opening editor’s note, “The driving force behind The Holy Hour is an attempt to get at the everything-ness of life, to capture this contradiction of sex work and make it understood on paper. It will always be missing something, but it will also always be perfect and timeless,” then she and Duffy have made an important attempt, missing something, but vital nonetheless, in this first edition of The Holy Hour. It is timeless. This anthology is a unique collection, one which will surely end up on feminist and cultural course syllabi in universities someday soon.

Get your copy of The Holy Hour here.

Bio: miss mirage, also known online as thepasteldomina, is a writer and the author of erotic semi-fiction stories such as 'reggaeton strap-on: a latina lesbian adventure' and 'his first escort: f*cking my favorite comedian.' a s*x worker for over a decade, she currently writes and records audioerotica for her devoted worshippers on patreon and manyvids, while working occasionally as a str!pper. she receives tributes from devoted subs and fans through https://throne.com/thepasteldomina. her erotica can be accessed via patreon through the web address: tinyurl.com/miss-mirages-world. you can take a peek into her beautiful world on fetlife with her username: thepasteldomina. find her on x: @pasteldomina

Are you a sex worker with a story, opinion, news, or tips to share? We'd love to hear from you!

We started the tryst.link sex worker blog to help amplify those who aren't handed the mic and bring attention to the issues ya'll care about the most. Got a tale to tell? 👇☂️✨