I still remember the day I plucked John Berger’s Ways of Seeing off a bookshelf. Its small size intrigued me. On the white cover was the small bold text of the opening lines. Even the book design was different from other books I’d read! I settled down later that night with it and came across a chapter that has stayed with me ever since.

In Chapter Three, Berger writes that being a woman involves always being watched by men. On top of that, women are always aware of being watched, so they act accordingly. “A woman must continuously watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by an image of herself. Whilst she is walking across a room… she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking… men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at… Thus she turns herself into an object – and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.”

Ways of Seeing isn’t just about women and men, it relates to how we see the world. Berger goes on to say that we can see how women are reduced to being “an object of vision” in traditional European art. In classical Western art, women are often naked for the viewing of the spectator. Paintings such as those of Nell Gwynne By Lely, commissioned by Charles the 2nd, show a naked woman passively looking back at the viewer. I remember seeing Bronzino’s An Allegory With Venus and Cupid in the National Gallery in London for the first time, and being struck by its beauty. I also remember noticing Venus’ excessively twisted body, naked for the viewer, before noting any of the symbolism in the background. As Berger says, “the way her body is arranged has nothing to do with their kissing. Her body is arranged the way it is, to display it to the man looking at the picture.”

What Berger doesn’t explain, is that many of the women posing for these paintings were sex workers. For example, Titian’s famous Venus of Urbino was modelled on Angela del Moro, a Venetian sex worker. Venus lies naked and passive, her body on display for the viewer to consume. Nell Gwynne may have stared passively from her portraits, but the woman herself was infamously anything but passive – she broke up a fight between her stagecoach driver and a man who called her a whore by saying, "I am a whore. Find something else to fight about.”

As Western art developed in the 20th century, artists such as Manet and Toulouse-Lautrec did explicitly paint sex workers. For example, Manet’s Olympia is a response to Titian’s Venus. Instead of lying shyly with her nakedness demurely covered like Venus, Manet’s model looks straight ahead at the viewer, hands blocking the viewer’s gaze and pleasure. But most art critics don’t interpret Olympia as a positive representation of sex workers. Most say that Manet was criticising other artists’ use and promotion of sex workers in art. That Manet was creative gritty social commentary on the immorality of sex work in his time.

As sex workers, we can see the irony in these cultural discussions. Traditional Western art has immortalised sex workers to be gazed at but to never look back. More straightforward depictions of sex workers such as in Olympia, are taken to be a commentary on the immorality of selling and buying sex. Yes, Manet created Olympia at a time when artists were making social critiques, but when I look at his painting, I see a woman looking back at her viewer. I see a woman blocking access to her nakedness until she is paid! This interpretation of mine isn’t a commentary on the morality of sex work in Manet’s time, but rather, a question. Art critics’ discussions, even when about the objectification of women in art, silence the sex worker who is part of the artwork. So what would Western art look like if we let the sex worker in it, speak for herself?

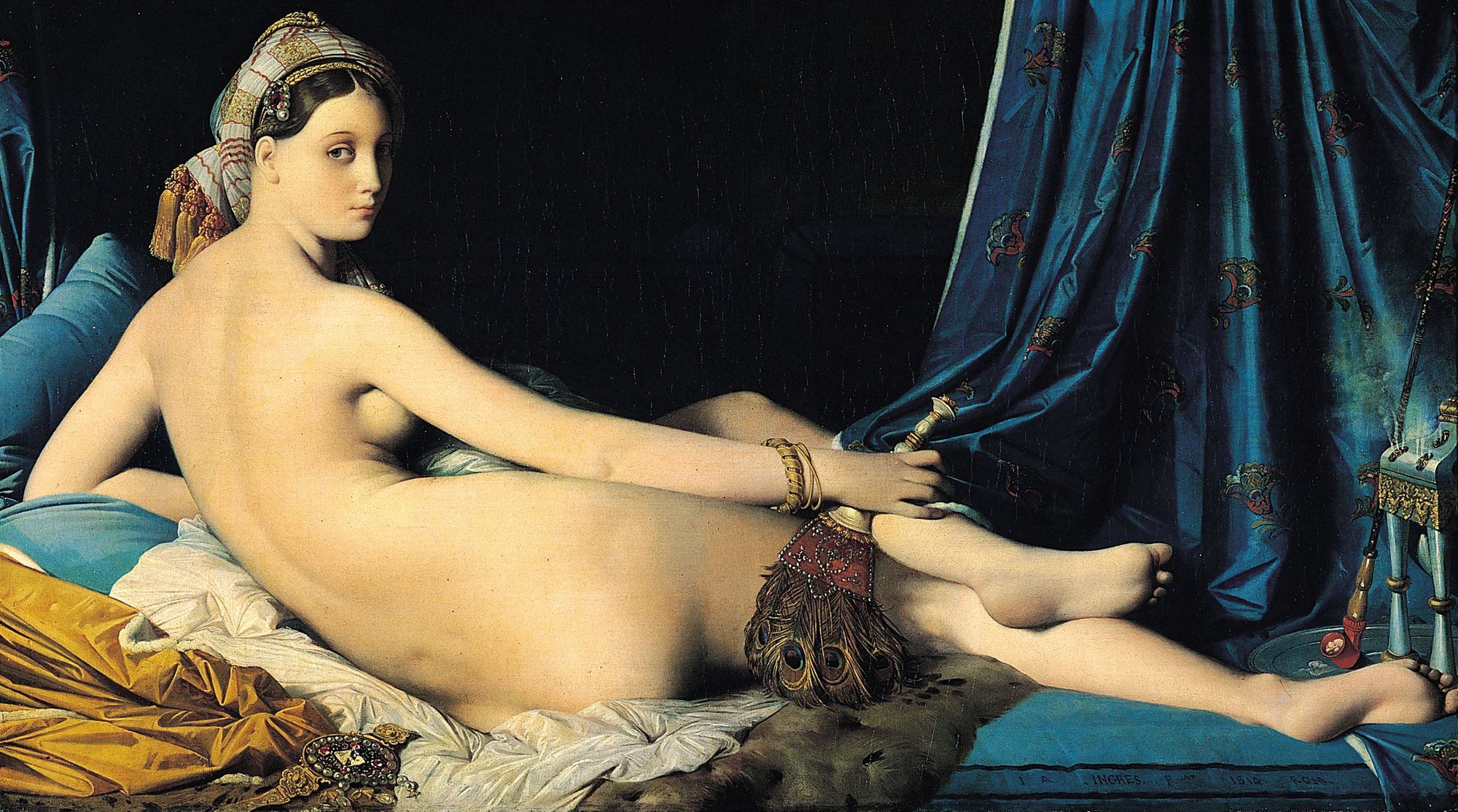

Feminist responses to Western art have usually failed to answer that question. In 1914, suffragette Mary Richardson slashed Velasquez’s Rokeby Venus, in a protest against the way men would “gawp” at it. Born in 1985, the anonymous feminist art group Guerilla Girls use a repurposed image of Ingres’ Odalisque bearing the text “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” Both the Rokeby Venus and Odalisque were naked paintings of sex workers, inspired in part by Titians’ Venus of Urbino. Western feminist art has often successfully commented on the objectification of women, but rarely on the unique objectification of sex workers.

Sometimes feminist art has gone even further by reducing sex workers to silent symbols of degradation. In Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, the sex worker protagonist spends copious time in view of the camera, getting ready for her clients. Unlike art by and for sex workers, she is not given an interiority beyond selling sex. Again, sex workers can see ironic parallels with our own position in today’s society. Women who sell their sexuality for the simple fact of work are not seen or heard, either by the viewers that gaze at them, or the feminists who protest against their viewers.

One of the wonderful things about art is that we can always make new meanings of symbols with it. Traditional Western art has typically objectified women, particularly sex workers, and mainstream feminist responses haven’t gone far enough to critique it. Just as Manet’s Olympia can be taken as either a moralising piece of art that damns sex workers, or a depiction of a sex worker who refuses to be objectified, sex workers can make our own meaning with our own art. We can follow traditional classical masters, or invent new forms entirely.

Many of us are artists - and through art, we can depict and view ourselves through our own eyes.

Are you a sex worker with a story, opinion, news, or tips to share? We'd love to hear from you!

We started the tryst.link sex worker blog to help amplify those who aren't handed the mic and bring attention to the issues ya'll care about the most. Got a tale to tell? 👇☂️✨