Editor's Note: this piece contains mentions of suicidal ideation.

I first read the idea of sex work having a binary of 'princess and prey,' in Madeleine Blair’s essay "Thin Walls" in The Holy Hour anthology. Blair writes, “…the irony isn’t lost on me that my decision to be a Whore is what has fastened me, joyfully, to an instant community – for being outsiders to those who, if they see us at all, view us as princess and prey.” Reading the words, I felt an instant flashback to a conversation I had over coffee with another sex worker in Berlin in 2023. We had been discussing sex worker stigma, and the way we each felt uncomfortable with what we saw as a new trend of having to pretend to be happy, carefree, rich bitches at all times. That sex worker summed it up for me perfectly, saying something to the effect of, “You either have to be the sexually fulfilled, financially dynamic girlboss, or the exploited victim.” These two dramatic and diametrically opposing poles reminded me of another trope: Madonna/Whore. Is Princess/Prey the new complex for sex workers? And how do we avoid falling into the trap of oversimplifying our experiences at either end of the spectrum?

Perhaps the best way for anyone to familiarize themselves with the idea of Princess/Prey is to look briefly at two movies portraying sex workers. First, the Princess: we all know it, and we love to hate it – Pretty Woman (1990). To fully examine all the ways in which Pretty Woman is problematic in its representation of sex work and provider/client relationships is beyond the scope of this essay. Let us focus on the core points: a street-based sex worker named Vivian encounters a man who is, “just looking for directions” (for those who don’t know, this is an embedded joke– “I was just looking for directions” is a common excuse used by Johns cruising in the United States when they are stopped by police in areas of street prostitution, as seen in Sean Baker’s film Tangerine). The man turns out to be fabulously wealthy, and decides to engage her services. He sweeps her off to a life of fancy hotels, where she consumes strawberries and champagne in a bubbly bathtub. He wakes her up by giving her his credit card and saying, “Time to go shopping.” They fly on a private jet to the opera. She goes on the iconic Beverly Hills shopping spree scene and ditches her thigh-highs for the wide-shouldered blazers and skirts that were chic among wealthy white women in the 1980s. Vivian attends horse races and wears pearls. At the end, the man climbs her fire escape and ‘rescues’ her the way she always imagined being rescued by a knight in her childhood fantasies in foster care. She becomes a princess.

Is Princess/Prey the new complex for sex workers? And how do we avoid falling into the trap of oversimplifying our experiences at either end of the spectrum?

This is the narrative which even some of our most ardent civilian supporters – in my experience, these tend to be sex-positive-positioned civilian cis women and queers – believe what it means to be a sex worker. They want to believe it. The idea that we are effortlessly flitting from wealthy client to wealthy client, scooping up oodles of cash and having lovely sexual experiences as an afterthought, makes them see us as empowered. By supporting us, it makes them, in turn, feel empowered. The current cultural moment, in which Pussy Rap (music by Megan thee Stallion, Ice Spice, Sexyy Red, Cardi B, the now-defunct City Girls, etc) reigns supreme, reinforces this kind of messaging. Lyrics like: Get your boots and your coat/for this wet ass pussy/pay my tuition just to kiss me on this wet ass pussy or He got some money then that’s where I’m headed/my pussy A1 just like his credit from WAP by Cardi B and Megan thee Stallion are motivating anthems for sex workers because they are relevant to aspects of the transactional nature of our work. For some of us, these lyrics speak directly to our experience, and the strong rhythms empower us to get out of bed and begin the routine which starts our day – or night – of work. As a Black female sex worker, the way in which Black women have quickly eclipsed male rappers in the rap industry and turned the “fuck bitches, get money,” era of music back on them is doubly empowering for me.

As sex workers listening to this music, we don’t ever misinterpret the reality of the many hours spent in preparation, advertising, photoshoots, and hustling which can lead us to successfully having our tuition paid or receiving expensive gifts. I feel that civilians, however, hear these lyrics and visualize a fantasy in which sex work in all of its myriad forms (stripping, camming, full-service, adult films, etc) is easy. My concern is that civilians, in an effort to be supportive, see the lives of sex workers as carefree – a montage of luxurious moments set to a backing track of Pussy Rap. I see this in the way civilian acquaintances who know I am a sex worker will greedily press me for stories of success from the strip club, while their eyes will glaze over if I mention anything ‘normal’ or non-titillating about work. They don’t ever want to hear, “It was boring,” or “I only made $100 last night and I was there for nine hours.” We hear it from civilians when they speak about their own work troubles and they casually say, “Maybe I should just sell feet pics,” half-jokingly, as a solution to their problems. I remember from my own days of young girlhood that I and my circle of schoolmates all thought that being a stripper must be an incredibly easy job for fast cash. “Maybe I’ll just be a stripper,” some of us would say, mostly to shock the others in our group (and of the six of us girls who had those conversations, two of us did actually become sex workers).

My concern is that civilians, in an effort to be supportive, see the lives of sex workers as carefree – a montage of luxurious moments set to a backing track of Pussy Rap.

This is all concurrent with a rise in the appropriation of sex worker aesthetics by celebrities and ‘pole-fit’ enthusiasts. I would argue that both social media and the fascination with sex workers (namely, strippers) online has also contributed to the building of the ‘princess’ archetype. And arguably, many of us workers – especially financial dominatrixes, strippers who have an online social media presence, and some online-only workers – also contribute to the idea of being ‘princesses’ as a necessary part of our marketing. No shade. It is what it is. My only concern is that in viewing our lives and work as carefree clickbait to ogle and cry “YAASS!” over, certain civilians create an escape hatch through which they can avoid listening to us talk about violence against sex workers, harmful legislation against sex workers, or sex worker rights within the context of labor rights movements. Sharing a findom or stripper TikTok, claiming a ’sex worker friend,’ going to a stripper-organized nightlife event, or taking a pole class, becomes a substitute for solidarity. Instead, I would be happy to see civilians taking action to advance the political rights of sex workers. Being a princess, after all, is not exactly a job (waiting for the members of various European royal families to drag me). It’s a title, which comes with privileges and certain responsibilities. But the word ‘princess,’ decries an absence of wage-labor which is not in keeping with the realities of sex work as work.

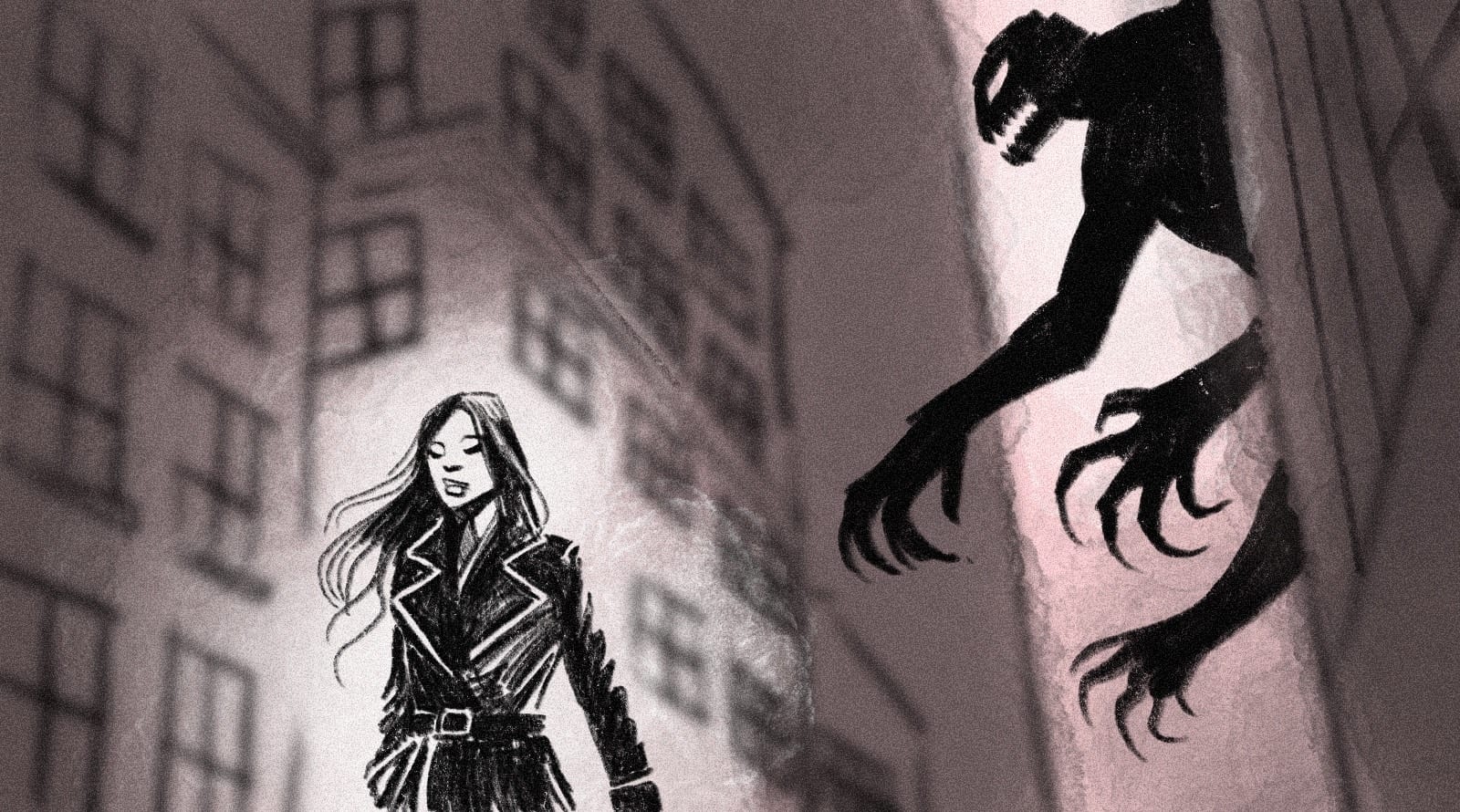

When we aren’t princesses, as Blair suggests, we are prey, those stumbling women in the darkness of the first shot of an episode of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. We are seen in the news as one of the many victims of serial killers who prey on sex workers, like Seattle’s Green River Killer, Alaska’s Butcher Baker, or Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside Killer. The movie Klute (1971), starring Jane Fonda, centralizes the idea of sex workers as prey. Fonda plays Bree Daniels, a call girl who is being called and stalked by a psychotic killer – one of her former clients. Donald Sutherland plays the private investigator who is simultaneously trying to save her and resist her sensual charms. The life of the sex-worker as prey, compared to that of the princess, is difficult. The prey, like Bree Daniels, navigates pimps and beatings. Her fellow colleagues face heroin addiction and death. In one scene, we see Bree from a high-angle shot – the killer’s viewpoint – as he stalks her from his position on her rooftop through her skylight. He is hunting her, and has already hunted down two of her coworkers. She is literally his prey. Bree Daniels and her two colleagues did a group session with this man, and now they are all paying the price. This is the message of the prey archetype: if you do sex work, you are doomed.

When we aren’t princesses, as Blair suggests, we are prey, those stumbling women in the darkness of the first shot of an episode of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit.

The idea of sex workers as victims, headed for (or born in) tragedy and who need to be saved, is so prevalent in the minds of many civilians that some of us workers expend a great deal of effort trying to avoid the idea of us as victims – diving headfirst, instead, into the princess archetype. To give one example from my own life, I once received the following feedback from a fellow sex worker about a performance I participated in: “That performance made me want to slit my wrists,” she complained about my and the other sex workers’ pieces. “Don’t you all know that’s what [the civilians] are coming to see?” I understood her point, in a sense. There are some civilians who are coming to see monologues by sex workers and expect to hear every trope of victimhood and trauma porn you can think of – abuse, neglect, sorrow, pain, self-hatred, etc. But what if I am actually sad? What if it took me some time to find my way to being empowered by my work? How can we as sex workers find a medium ground of telling our stories which is authentic to our experiences, and shows us not as fantasy princesses or shivering victims but as nuanced human beings?

For clients, I can see that at least in the context of the strip club, the Princess/Prey complex influences their choice in who they wish to spend time with. Some are indeed in the club looking for a glamorous princess-type they can drink champagne with and take on shopping sprees. Others are seeking to be captain-save-a-hoe. It is up to us as dancers to sniff out which fantasy the client is looking for us to fulfill, and to play the part. Like Vivian in Pretty Woman, Bree Daniels’ story ends with her leaving sex work, followed by a presumed marriage to her white knight and a move to an affluent life in the suburbs. If the ideas of us as either Princess or Prey have anything in common, it is that ultimately, we are still in need of rescuing. Both ends of the spectrum lack nuance about our experiences. What we can do as sex workers is keep trying to create our own narratives which exist outside of complexes and oversimplified stereotypes, while still doing whatever marketing we need to do to run our business. The responsibility, after all, isn’t solely on us – it is up to civilians, those who support us and those who don’t, to push further than the simple stories told about us by non-sex workers and to try to understand some authentic version of our truth.

Are you a sex worker with a story, opinion, news, or tips to share? We'd love to hear from you!

We started the tryst.link sex worker blog to help amplify those who aren't handed the mic and bring attention to the issues ya'll care about the most. Got a tale to tell? 👇☂️✨