Contains spoilers

“Pretty Woman glamourises prostitution.” So common was this response to the most infamous of pop-movies about sex work, it had the tone of an idiom. I don’t know how often it was actually said or if anyone still believes it today. Of course, it’s not prostitution that it glamorises, but romanticism and consumerism. It uses aspirational materialism as a veil over its ambivalent attitude towards the marginal role of the paid mistress.

The film, like bourgeois society more broadly, undermines explicit sex work but is equivocal about more camouflaged, expensive forms. Women using their charms in return for wealth adjacency, is still lay-for-pay by any other name. And yet, it encompasses major facets of capitalist ideology: competitive femininity, exceptionalist individuality, and social mobility.

Vivian (Julia Roberts) walks the streets of Hollywood Boulevard in a champagne-blonde wig. She lives in a rundown low-rise. On the beat, she encounters a dead colleague “pulled out of a dumpster.” She makes $100 an hour but has “a safety pin holding her boot up.” Her life isn’t glamorous; it is precarious. She has no money, no security, and her fellow survival sex workers are unsympathetic. Even her roommate–the witty Kit de Luca (Laura San Giacomo)--is presented as drug dependent and unreliable.

Vivian is ‘rescued’ by Edward (Richard Gere), a financier with a Vampire Lestat handsomeness driving a Lotus Esprit through the Boulevard. He’s a bad driver and grinds to a halt. Vivian mistakes him for a potential client. He intends on ignoring her, but she charmingly charges him for directions. She can do anything baby, she ain’t lost. And though Edward looks put out, it is a shallow irritation. Vivian’s charging for directions makes him feel safe that she is sufficiently entangled into transactional thinking, that she poses no intimate threat. Hence, the emotionally avoidant money maker barely blanches when she invites herself into the car and directs him to his luxury hotel.

Despite himself, he invites her into his world. He takes her to the penthouse, offers her $3000, expensive shopping trips, and the Cinderella treatment. He is touchingly pleased when this pretty guttersnipe is whimsically impressed by his big room and his big tub. Edward is tired of all the rich and indifferent sophisticates with the lethargy of the over-indulged.

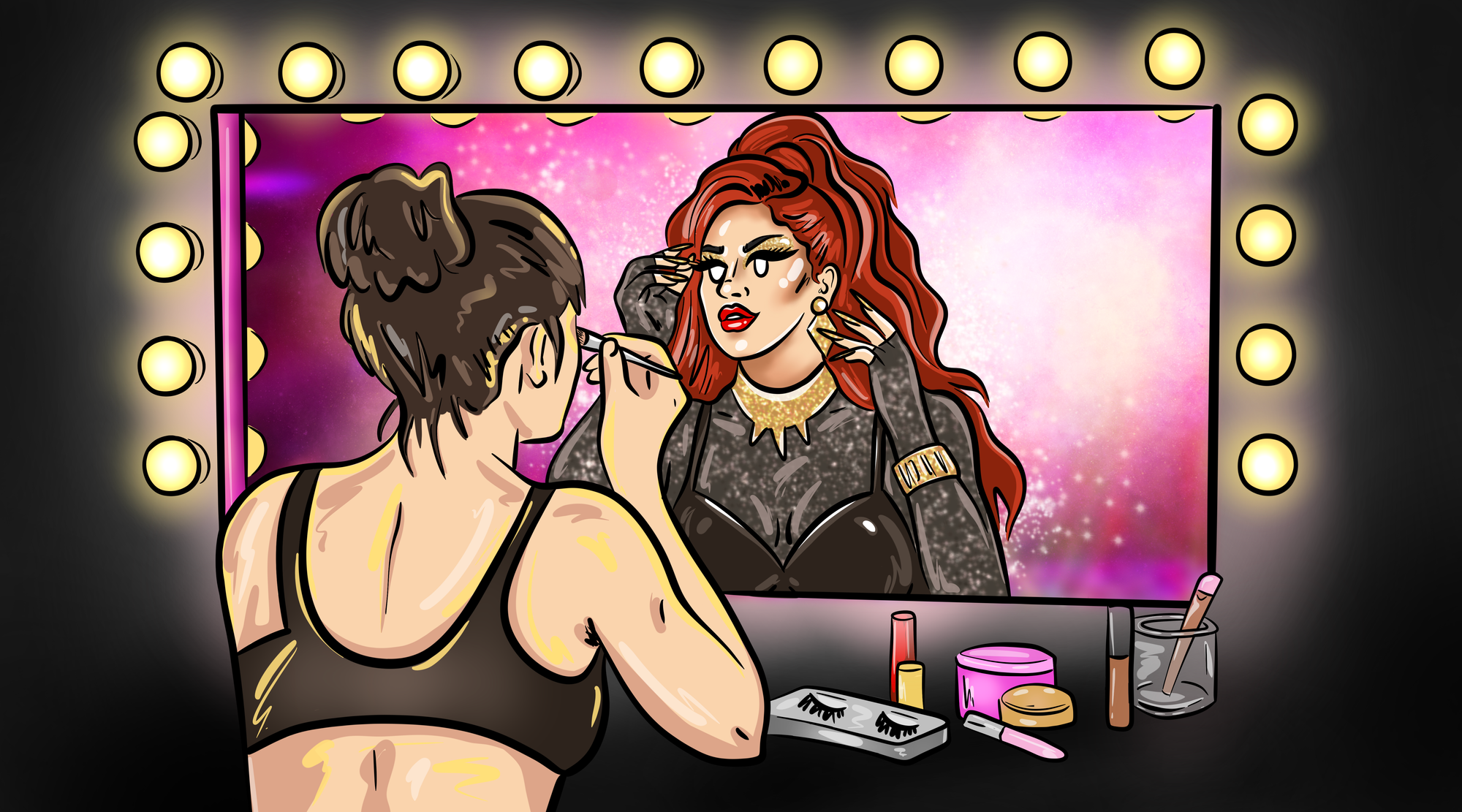

Vivian doesn’t sustain her naivety for long; she adapts into bourgeois ideals–the early 1990s consumer glow-up. With the aid of his credit, the transgressive imagery of street-based sex work is symbolically cut and buffed by luxury fabrics, refined hairstyles, and shimmering necklaces with obnoxiously large price-tags. It’s through this process that the possibility of ‘love’ is reckoned with. The consumer baubles are endowed with romanticism, in much the same manner as any engagement ring advert you ever saw. Vivian becomes a romantic heroine through them, and the reality of their sexual exchange is obscured.

Thus, the romanticisation of consumerism serves as a diversion that hides the economics of love; in Vivian’s world, as in ours, love is not primed to breed intimacy but to collate wealth and confer status. Romance and consumerism are elements that have been used to paper over our political-economy’s blunt force. Shiny things decorating our culture of power for power’s sake, like the bright lights that prettify the nightly vista of the concrete jungle.

Sex work is thought to be problematic because it exposes what is meant to exist only in the basement room of capitalism. In Marxist theory, the economics of life are submerged below a dreamy culture of perfect fantasy. We call this ideology. The seductive bits are meant to stay front and centre–fashion, lifestyle, luxury, romance–and the ‘deal’ is obscured into the dry, murky corners. The hooker on Hollywood Boulevard offering an hour of her sex appeal for $100 is disturbing the dynamic with the explicitness of the exchange.

To add to the controversy, she is more often than not a woman. This is no small point. Femininity is a primary language of consumer-capitalism. Elegant feminine bodies are used, from billboards to video-blogs, to inspire an idealism that encourages consumption. But they are not meant to actually be consumed. They are meant to be, like a mirage in a desert, always out of grasp. Feminine perfection inspires a relentless pursuit of a vague utopianism that leaves an always-itch. Sex work offends because it reveals the scratch. Not only is romance an ideology of capitalism, but women are tasked with being its moral guardians. We are meant to ‘buy in’ and defend the honour of the fantasy with piety. We are not to understand, let alone consciously, and willfully express its mechanisms.

How can ‘respectable’ society justify the audacity to stigmatise sex workers whilst cheering-on women who implore their fiancés to buy them diamond rings because they are ‘worth it’? By emotionally bejewelling the romantic exchange with ‘pretty things’ that are meant to signal phoney sentiment? What we have in Pretty Woman is not a sex worker moving away from ‘the life’, it’s the process of repackaging her persona to make her transactional relationship with Edward more digestible, more ideologically refined.

Indeed, the film still hypocritically beats over our heads unashamed sex work’s moral dangers. Other than Vivian, it is strongly implied that her Boulevard colleagues are forever marked by chaos. And yet, Viv is positively altered by financial benefaction. When she finds a slice of economic security and doesn't have to survive minute to minute, she can become more confident. This begs the question: wouldn’t all of her survival sex work colleagues benefit from some wealth redistribution? But in no universe would a film that vaunts consumerism want to better acknowledge the deep economic inequality between its protagonists. It has to maintain the illusion that it exists because of a natural moral inequality.

Edward is, in effect, a self-made man. And Viv? Yes, her fortunes are turned around by nabbing the affections of a wealthy client, but it is implied that this is only available to her because there is something about her.

We’ve all heard the misogynistic phrase, “she is not like other girls.” Pretty Woman specifies this to the sex industry; Vivian is ‘not like other whores’. Kit de Luca tells us, when she encounters her old friend in a designer suit, “You clean up real nice. You sure don’t fit in down on the Boulevard lookin’ like you do, not that you ever did.” The idea is that bourgeois society can make an exception for Vivian, not because her economic station has been elevated and she can better perform the role of elegant socialite, but because of her ‘specialness’.

Why Viv? She has the basic ingredients of the main character of romantic fantasy: beautiful, but it’s an earthy rather than an ice-queen beauty; bright, but not examining or analytic; unpretentious yet unabrasive. She wears her charisma haphazardly; she has it, she drops it, she picks it up again. Her occasional lack of co-ordination is a symbol. She has currency, but that fact seldom sinks in. She’s playful, and a touch naïve. She doesn’t quite fit the classic indie archetype of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl because she isn’t quirky as such, but she fulfils a similar role. She breezes into the man’s life in order to shake him out of his depression and to re-ignite him with the blisses of humanistic experience.

Despite his cold and controlling tendencies, Vivian develops feelings for Edward. She thus pales when he offers to give her credit cards and “put her up in a great condo.” She rejects the explicitness of the offer and waits for him to return to the table when he brings roses as well as riches. When I was a teen, I sympathised fully with Vivian. Love is the answer. But as a mature woman? If I’d spent the week with a rich, classy guy who I knew cycled through women faster than I speed through coffee pods, I’d be getting ready to negotiate my end-of-contract redundancy terms.

But in the fantasy, the questionable assurance offered is that the female lead is so above all other women in romantic desirability, she need not get down to brass tacks and work out her terms. To do so would continue the visibility of the ‘stain of prostitution’. The end of the film is not, as is softly implied, that Vivian is no longer a sex worker. Instead, that she has internalised the presumed moral failing of sex work and has agreed to suppress her business-mindedness in return for a vulnerable stake on the outskirts of respectable society.

Bourgeois society does not oppose sexual transactions; it is built on them. Rich men marrying the daughters of other rich men and keeping beautiful or sexually exciting mistresses on the side is the core sociology of the wealthy. The marriages are packaged as moral or romantic and the affairs and arrangements kept as hushed-up intrigues or spilled out as seedy gossip. It is the women themselves, not the dynamic as a whole, who are treated to the lion’s share of the blame when things don’t work out.

Someone has to absorb the moral hypocrisy, and it won’t be Edward. Nevermind what happens after the happy ending, even if Vivian’s material conditions are meaningfully improved by her elevation, which they are. And this is no small thing. When Vivian, the survival sex worker, enters a designer store in her white cut off top and red jacket tied about her waist, she is refused service. When Vivian, the well-paid mistress, walks through the grand foyer of the Regent Beverly Wilshire in white evening gloves and red gown, she is looked upon with approval. Approval isn’t just a perk, it’s the ability to move through the world more freely. Early Viv is restricted to troubled places. Wealth-adjacent Viv can go to operas, designer stores, polo events.

The vulnerability of her role as sex worker in ‘a man’s world’ never quite leaves her–as the sinister sexual assault scene with Edward’s lawyer Stuckey (Jason Alexander) reminds us. Becoming the mistress of a wealthy man does not offer her total freedom, but a new, more nuanced kind of marginality: the delicate task of having to continue to perform acceptability to retain her material comforts instead of the precarity of trying to relentlessly chase down the rent.

So, Vivian walks out on Edward. While consumerism is enough to improve her access in the world, it isn’t enough to still her unease about her social position. She needs a more clear-cut bit of romanticism to drape loosely over the cracks, like a gossamer cloth over a coffee stained table-top. Not a good client (something real) but a white knight (something dreamed). Which is why in the final scenes, after Edward hands back the borrowed diamonds to the hotel manager, he chases his lover down with a rose.

In many ways, romance is a more powerful capitalist ideology than consumerism alone. Pretty things are at least materially real. They can constitute an amusing distraction from the uncertainty of life, offer comfort whilst we fight to keep the wolves from our doors. But they can also be used, spent, lost. The ‘happily ever after’ is pure, unfalsifiable fiction. In the pre-Disney script named 3000, Vivian and Edward fight when the latter refuses to be romantic and the former soothes herself by taking herself on a coach to Disneyland. The bubble-gummed version subtextualises the inevitable heartbreak with a wry wink; the final film ends with the lovers embracing and the camera panning off to a denizen of the Boulevard shouting out, to no-one in particular, “Everyone who comes to Hollywood has a dream. What's your dream?” The condo awaits.

Are you a sex worker with a story, opinion, news, or tips to share? We'd love to hear from you!

We started the tryst.link sex worker blog to help amplify those who aren't handed the mic and bring attention to the issues ya'll care about the most. Got a tale to tell? 👇☂️✨