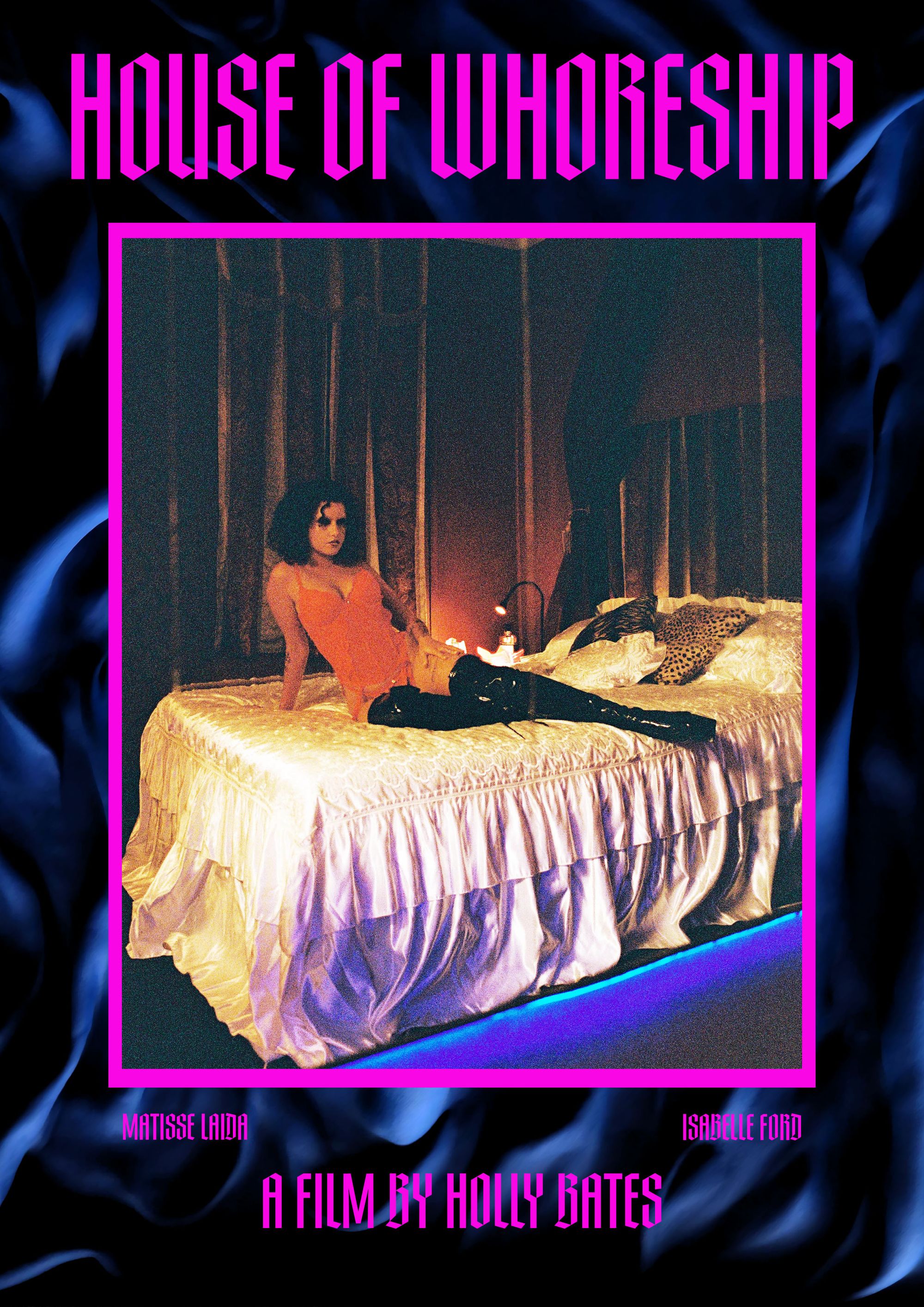

Mia Walsch: Can you tell us about your film, House of Whoreship?

Holly Bates: House of Whoreship follows the journey of brothel worker Violet as she endures an awkward night’s shift working alongside her recent ex-girlfriend/ co-worker Charlie. As the shift progresses she faces multiple obstacles, such as: running out of dexies [dexamphetamine], stubborn period sponges, witnessing her ex flirt with other workers – but ultimately she makes it through. It’s my first attempt and venture of creating relatable sex worker representation on screen through exploring camaraderie and community in the workplace.

Why did you want to tell this story?

House of Whoreship was born out of an earnest, deeply personal ambition to shift the current narratives surrounding on-screen sex worker portrayals. Sex work has been a part of my life, in one form or another, for 10 years now. Reflecting upon my growing interest in filmmaking over the past decade, I’ve contemplated the inner emotional conflict over the way my lived experience as a sex worker has been translated to the medium in which I aspire to work in. Historically every time my peers and I have faced our portrayals on the screen, we emerge distressed and disappointed. The sex worker community continues to bear witness to misinformed, disempowering, violent and two-dimensional representations of our lives; our on-screen depictions reinforcing criminalisation and patriarchal oppression, deeply affecting our livelihood and on a larger scale, our working conditions. As an industry that for the most part depends on anonymity for the safety of both its service providers and its clients, most people turn to the screen to gain insight. I wanted to tell the simple story of the uncomfortable consequences that come from dating and breaking up with a coworker because it's a universally relatable experience. Taking that universal experience and adding in the story context of a Melbourne brothel was a way to avoid whorephobic story tropes, and also educate mainstream audiences. Film has also canonically centred around the client’s perspective, often pushing the false fantasy that workers constantly fall in love with clients and desperately await their rescue. I wanted this film to convey the more common truth – that clients barely exist for us behind the scenes because we are too busy falling in love with each other!

Queer sex worker relationships are one-of-a-kind. What did you want to show about this dynamic?

I wanted to show the unspoken relatability and understanding in this dynamic, while also speaking to the camaraderie that persists despite essentially competing against each other for money. Queer sex workers are highly skilled in performing a straight persona as a result of the predominant heteronormative narrative that we grew up with. There’s a constant flux of the ‘performative’ and the ‘behind the scenes’ within the brothel environment. The performance can get exhausting, and so there's a sense of relief not just in the understanding of the work, but that you as a queer worker may have to put up more of a performance than other workers. You can find solace within each other. Sometimes there are straight sex workers you have to keep the performance up with too, which can be just as exhausting as being with a client. I also wanted to depict the desire of the queer gaze within the workplace, which is often camouflaged unless another queer worker spots it. Culturally, the film touches ever so slightly on issues with monogamy, which was a direct reference to the queer scene in Melbourne which is heavily dominated with the current buzzword and ethos of ‘ethical non-monogamy’. Although my own personal history of dating other sex workers has been very monogamous, this was a funny contextual story choice.

The intimacy between sex workers is often physical and emotional, and it doesn’t run on the same time frames as civilian friendships do. How did you try to illustrate this in the film?

Directing House of Whoreship, I was keen to work with filmic methods that challenged the traditional male gaze of objectifying feminine bodies, pre-eminently considering a majority of the actors would perform semi-nude characters. Celine Sciamma was a huge inspiration following research around her discussions regarding ‘the female gaze’, in which she explained methods to guide audiences to ‘feel’ the characters and their desires over objectively ‘seeing’ them. Visually, I set out to achieve this by favouring a mostly free-hand camera approach and lingering close-ups, aiming to capture the emotional spaces within the micro mannerisms and non-verbal exchanges that reflect worker interactions and additionally, queer desire. With the camera freely tracing character’s movements I aimed to reflect Sciamma’s methodology in connecting the audiences to character complexity and agency, in the hope of seeing past the societal taboo and emotionally empathising with the relationships built. In terms of story, I tried to illustrate the difference in worker friendships to civvie friendships through Violet’s interactions with characters in response to the obstacles she was facing. No matter what interpersonal tension she was experiencing with another worker, the gestures of help or solidarity remained consistent.

It’s also made clear by the receptionist early in the film that this is a 24-hour brothel and intros are called by reception constantly. Interactions between characters are frequently interrupted by the intercom. These constant interruptions illustrate how time runs differently in worker-worker friendships because we are so used to multitasking within our interactions, always ready to pause and pick back up at any given moment.

I started out thinking the film would be about money, but it ended up being about friendship. How did you want to challenge stereotypes in HOW?

We all know that as sex workers, our primary reason for getting into the industry is money. However, one of the things I loved most when I started brothel work is that despite the brothel (and industry) being a melting pot of vastly different identities and hooker origin stories – is that there were a lot of parallels and common threads in worker’s slutty personal histories.

I found a place where I could bond with people over being the girl who slept with the entire friendship group, who was sexually curious and shamed for it in highschool, who sexted her sports coach. A history that had previously had shame imposed on it by others made lighter, made funnier, made relatable.

I went into sex work for a variety of reasons, but the community and validation I found in the industry totally took me by surprise. I felt more accepted in this community than I did when I first entered the queer community. Occasionally clients make a shift memorable, but the experience of going into the backroom to de-brief the booking with other workers is often more fun than the booking itself. In film and TV it’s often depicted that the workers are seeking mental salvation from their workplace through a booking with a client they deem to be safe- sometimes even being rescued from the workplace by the same client. I wanted to challenge this stereotype by simply depicting a sex work environment where issues come up and are dealt with like any other workplace, and colleagues support each other in the process. There’s no saving needed, we have all the support we need within the community.

I read an interview recently where you said that the closed brothel you shot in was bare besides the bed frames and soap dispensers, but the set was so realistic, especially the locker room. What was the process of set dressing like? Did you pop in any easter eggs?

The process of set dressing was pretty long and gruelling, given there was a whole building to cover and we were using most of it! Production designer Renee Kypriotis and I worked together to source most of the items from facebook marketplace. I was very meticulous in my vision and Renee did a fantastic job executing all the specific details while also adding her own creative flair. We bought a reception desk from a nail salon that had a hand embellished on it which I requested fake nails be made and added to. I micromanaged the production design because it was so important to me for it to accurately reference the real deal, which probably made me a pain to work with. I remember the day we were shooting the shower cleaning scene, and the production design team had picked up a sponge to clean the shower instead of a squeegee. The shoot was slightly delayed that day because I asked a production assistant to run to Bunnings to grab a squeegee, because it just wasn’t RIGHT without it, you know?! Decor wise, there’s a couple of Madonna Whore Complex and other worker-made artworks in the backroom, a Britney Spears perfume bottle on the vanity counter, a passive aggressive sign about not flushing sponges next to the toilet, etc. A lot of my own work gear and belongings made their way onto the set. The easter eggs are there if you look closely.

I loved the attention to detail in the film. When Violet finishes her booking, she’s cleaning the shower and she’s got the towel on the floor, then uses her feet to dry the corners - like every sex worker ever. How important were these little details in the film? What do these everyday details tell us about the work of sex work?

These details were important not only in their mundaneness, to emphasise the ‘work’ aspects, but also to humanise sex workers as legitimate workers. Depictions on screen of sex work are usually highly over dramatised and focus primarily on the stigmatized elements, making it seem scary and unrelatable to civvies. Focusing on tedious tasks and details made the world seem much more approachable to the mainstream – while also being more realistic and relatable for workers too.

What was the experience of filming in a team that was a mix of sex workers and civilians?

In accordance to my goal of collaborating with local film-industry workers, my team and I sought out local pro-sex work clothing brands and creatives for wardrobe and post-production, as well as sex worker-made artworks for set design. A primary objective was for House of Whoreship to not just exist as a production, but rather an ecosystem of collaboration in which artists supported artists. This has since proved to be an effective marketing technique in reaching the key audiences, through digital word of mouth in collaborators and brands promoting their work within the film.

The crew I hired was also mostly femme and queer – which doesn’t automatically mean sex worker friendly, but it does increase the odds. I did my best to vet out each potential crew member.

My approach to directing was very hands-on, consulting heavily with all departments. As a director I encouraged feedback and collaboration, and often sought technical advice from the more experienced crew members. Some actors offered alternative lines and enactments of character I was excited to play with. I was flexible with adapting shots, design and direction, so long as they ultimately served the story. My goal with directing was to provide an experience that all cast and crew members felt they gave voice to, with the ambition for everyone involved to depart feeling valued and proud of the work we had created. Through employing an intimacy coordinator and having had work experience in that department myself, I believe we were able to achieve strong intimate and vulnerable content from the actors throughout the production as well as provide a safe workplace for all.

After shooting, a few sex worker-crew members confided it was the only film set they had felt safe to be ‘out’ working on. I discovered just how many sex workers exist in the film industry who are desperate to contribute to representation in film but aren’t in the position to be out. For the majority of the crew who weren’t workers, I learned that they didn’t know much about the industry, and almost all their information had been gained from film. I provided a number of books and texts written by sex workers in the green room, so the crew could educate themselves and prevent them asking additional labour from the sex workers on set in educating them.

The lingerie a worker wears is so important, it says a lot about them and the way they work, and is so personal and individual. How did you decide on costumes for each character?

I had moodboards for make-up and costume for each character based on their personality traits, in addition to a list of sex-worker used brands in Melbourne for the Wardrobe stylists Katherine Rose and Kiki Wenzel to go off – but otherwise I let them take creative control with the wardrobe. They were fantastic in pulling the looks together. They had multiple options for each actor, and consulted with each actor what outfits they felt most comfortable and sexy in. This was important because as a worker feeling sexy and confident really helps with the hustle, and outfits can play a major role for getting into that headspace. That same mentality and method applied for the actors too. It was good to relinquish control a little bit so the stylists and make-up artist Wendy Nguyen could camp up the looks and make it just a touch more fantastical than real life. I wanted the dressing gowns to be super woolly and daggy, but had to compromise when the wardrobe team opted for silk dressing gowns for aesthetic consistency. I’ll save the daggy, well-loved communal dressing gowns for the next production. They can have a star role!

What has the reaction to the film from sex workers been like? How about the reaction of civilians?

Funnily enough workers often mention the shower scene and the squeegee, so there have been some reactions that have really validated my attention to detail even if my civvie crew members or uni teachers didn’t understand the importance. At the recent sex worker festival we screened at in Naarm, ‘Love, War & Theatre’, I heard audience members whisper about the outfits, and there was the most amount of laughs to worker dialogue in comparison to the civvie festivals I’ve shown at. I don’t think I’ve experienced a negative reaction to the film from a sex worker yet. Sex workers have been so supportive of a worker made film in principle that it’s made me feel more connected to the community than ever.

Civvies have reacted fairly positively too – they seem to be most taken back by the everyday elements depicted, but also how wholesome the story ends being as a whole. I don’t think their previous perceptions could conceive that a concept like ‘wholesome’ could be a common occurrence in the brothel environment. One civvie woman did make a point of saying to me she was surprised we had showers… but every honest and open reaction from civvies has been super illuminating in what components of the job need to be covered in future films. Sometimes when you’ve been in the industry so long you forget the certain elements civvies may be unaware of.

Face out sex workers experience barriers to travel. What was it like not being able to travel to the US, and what did that mean for the promotion of HOW?

It’s been disheartening, given the US is a prominent figure in the film industry, but it’s also been inspiring in creating a career path without stepping foot in the US because… fuck the US.

When I was in Canada for the film’s premiere, I was able to meet some lovely American film-makers, and one of them offered to hand out postcards for me at CineKink festival in NYC which they were also showing with. I’ve made connections where I can, and I’ve done a lot of online hustling and marketing. I’ve been successful in promoting it over there on a small-scale as a result. Film involves a lot of creative problem solving, and dealing with this travel barrier has just further enabled me to use that skill.

We hear you are planning a follow up. Can you share a bit about where you would like to take the series?

I have ideas for scenes, characters and parts of sex work that are under-represented for the next production, but I don’t have a grand idea of where it will go. I’m not setting my sights on a sole vision just yet, because I’m working with other writers for the next one so we can achieve even more representation and platform for more voices. As filmmaking is very expensive and time consuming, we can only afford to make one short film instalment at a time. The building we shot House of Whoreship in is off the market now, and the temporary nature of film locations will most likely mean we will need a new location for each film. This opens up the possibility of creating stories in other sex working locations such as massage parlours, dungeons, escort/private work etc.- especially with other writers on board. I spent a lot of my time last year hustling and promoting House of Whoreship to give it the best shot possible. I’m excited to step away from that now, get back to the creative process and finally write something new, but of course, still slutty.

***

Holly Bates is a Naarm/Melbourne-based emerging filmmaker, visual artist and sex worker. Bates recently completed a Masters of Film and Television at the Victorian College of the Arts, graduating with first class (2022). Her graduate film and directorial debut House of Whoreship had its World Premiere at Inside Out Festival (2023), followed by 20+ film festival premieres internationally, 3 premieres nationally, with additional premieres fast approaching.

Holly’s solo art practice has exhibited nationally in Australia at spaces such as BLINDSIDE Art Space, Boxcopy Contemporary Art Space and Metro Arts. Furthermore her collaborative practice Parallel Park has showcased at spaces such as Airspace Projects, UNSW Galleries, BUS projects, La Trobe Art Institute, Carriageworks and the 2021 Rising Festival. Bates has appeared in publications such as UN Magazine, Eyeline Magazine and recently was interviewed by VICE.

Bates’s creative practice aims to dismantle and challenge the toxic film tropes historically used to depict sex workers on screen. Employing filmic methods that abandon the male gaze, Bates seeks to empower workers; honing in on the complexities and subtleties of interpersonal relationships and the day-to-day lived experience within the sex industry. Artist and filmmaker, Bates is driven to create conceptually rich worlds and stories, layered for both sex worker and mainstream audiences. Using humor and intersectional approaches to film-making, Bates explores personal narratives that are informed by her position as a queer feminist.

Are you a sex worker with a story, opinion, news, or tips to share? We'd love to hear from you!

We started the tryst.link sex worker blog to help amplify those who aren't handed the mic and bring attention to the issues ya'll care about the most. Got a tale to tell? 👇☂️✨